|

|

History of Textiles.

Textiles have been important in human history and reflect the materials available to a civilization as well as the technologies that it has mastered. The social significance of the finished product reflects their culture.

Textiles, defined as felt or spun fibres made into yarn and subsequently netted, looped, knit or woven to make fabrics, appeared in the Middle East during the late stone age. From ancient times to the present day, methods of textile production have continually evolved, and the choices of textiles available have influenced how people carried their possessions, clothed themselves, and decorated their surroundings.

Ancient textiles and clothing

The first actual textile, as opposed to skins sewn together, was probably felt. Surviving examples of Nålebinding, another early textile method, date from 6500 BC. Our knowledge of ancient textiles and clothing has expanded in the recent past thanks to modern technological developments. Our knowledge of cultures varies greatly with the climatic conditions to which archeological deposits are exposed; the Middle East and the arid fringes of China have provided many very early samples in good condition, but the early development of textiles in the Indian subcontinent, sub-Saharan Africa and other moist parts of the world remains unclear. In northern Eurasia peat bogs can also preserve textiles very well.

Ancient Near East

The earliest known woven textiles of the Near East may be fabrics used to wrap the dead, excavated at a Neolithic site at Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, carbonized in a fire and radiocarbon dated to c. 6000 BC.Evidence exists of flax cultivation from c. 8000 BC in the Near East, but the breeding of sheep with a woolly fleece rather than hair occurs much later, c. 3000 BC.

Ancient India

The inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization used cotton for clothing as early as the 5th millennium BC – 4th millennium BC.

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition:

"Cotton has been spun, woven, and dyed since prehistoric times. It clothed the people of ancient India, Egypt, and China. Hundreds of years before the Christian era cotton textiles were woven in India with matchless skill, and their use spread to the Mediterranean countries. In the 1st cent. Arab traders brought fine Muslin and Calico to Italy and Spain. The Moors introduced the cultivation of cotton into Spain in the 9th cent. Fustians and dimities were woven there and in the 14th cent. in Venice and Milan, at first with a linen warp. Little cotton cloth was imported to England before the 15th cent., although small amounts were obtained chiefly for candlewicks. By the 17th cent. the East India Company was bringing rare fabrics from India. Native Americans skillfully spun and wove cotton into fine garments and dyed tapestries. Cotton fabrics found in Peruvian tombs are said to belong to a pre-Inca culture. In color and texture the ancient Peruvian and Mexican textiles resemble those found in Egyptian tombs."

Woven silk textile from tombs at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan province, China, from the Western Han Dynasty, 2nd century BC

Evidence exists for production of linen cloth in Ancient Egypt in the Neolithic period, c. 5500 BC. Cultivation of domesticated wild flax, probably an import from the Levant, is documented as early as c. 6000 BC other bast fibres including rush, reed, palm, and papyrus were used alone or with linen to make rope and other textiles. Evidence for wool production in Egypt is scanty at this period.

Spinning techniques included the drop spindle, hand-to-hand spinning, and rolling on the thigh; yarn was also spliced. A horizontal ground loom was used prior to the New Kingdom, when a vertical two-beam loom was introduced, probably from Asia.

Linen bandages were used in the burial custom of mummification, and art depicts Egyptian men wearing linen kilts and women in narrow dresses with various forms of shirts and jackets, often of sheer pleated fabric.

Ancient China

The earliest evidence of silk production in China was found at the sites of Yangshao culture in Xia, Shanxi, where a cocoon of bombyx mori, the domesticated silkworm, cut in half by a sharp knife is dated to between 5000 and 3000 BC. Fragments of primitive looms are also seen from the sites of Hemudu culture in Yuyao, Zhejiang, dated to about 4000 BC. Scraps of silk were found in a Liangzhu culture site at Qianshanyang in Huzhou, Zhejiang, dating back to 2700 BC. Other fragments have been recovered from royal tombs in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC).

Under the Shang Dynasty, Han Chinese clothing or Hanfu consisted of a yi, a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash, and a narrow, ankle-length skirt, called shang, worn with a bixi, a length of fabric that reached the knees. Clothing of the elite was made of silk in vivid primary colours.

The textile trade in the ancient world

The exchange of luxury textiles was predominant on the Silk Road, a series of ancient trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting East and West by linking traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from China to the Mediterranean Sea during various periods of time. The trade route was initiated around 114 BC by the Han Dynasty,[24] although earlier trade across the continents had already existed. Geographically, the Silk Road or Silk Route is an interconnected series of ancient trade routes between Chang'an (today's Xi'an) in China, with Asia Minor and the Mediterranean extending over 8,000 km (5,000 mi) on land and sea. Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of the great civilizations of China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, the Indian subcontinent, and Rome, and helped to lay the foundations for the modern world.

Iron age Europe

The Iron Age is broadly identified as stretching from the end of the Bronze Age around 1200 BC to 500 AD and the beginning of the medieval period. Bodies and clothing have been found from this period, preserved by the anaerobic and acidic conditions of peat bogs in north-western Europe. A Danish recreation of clothing found with such bodies indicates woven wool dresses, tunics and skirts. These were largely unshaped and held in place with leather belts and metal brooches or pins. Garments were not always plain, but incorporated decoration with contrasting colours, particularly at the ends and edges of the garment. Men wore breeches, possibly with lower legs wrapped for protection, although Boucher states that long trousers have also been found. Warmth came from woollen shawls and capes of animal skin, probably worn with the fur facing inwards for added comfort. Caps were worn, also made from skins, and there was an emphasis on hair arrangements, from braids to elaborate Suebian knots. Soft laced shoes made from leather protected the foot.

Industrial revolution

During the industrial revolution, fabric production was mechanised with machines powered by waterwheels and steam-engines. Production shifted from small cottage based production to mass production based on assembly line organisation. Clothing production, on the other hand, continued to be made by hand.Sewing machines emerged in the 19th century streamlining clothing production.In the early 20th century workers in the clothing and textile industries became unionised. Later in the 20th century, the industry had expanded to such a degree that such educational institutions as UC Davis established a Division of Textiles and Clothing,The University of Nebraska-Lincoln also created a Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design that offers a Masters of Arts in Textile History, and Iowa State University established a Department of Textiles and Clothing that features a History of costume collection, 1865–1948. Even high school libraries have collections on the history of clothing and textiles.Alongside these developments were changes in the types and style of clothing produced. During the 1960s, had a major influence on subsequent developments in the industry. Textiles were not only made in factories. Before this that they were made in local and national markets. Dramatic change in transportation throughout the nation is one source that encouraged the use of factories. New advances such as steamboats, canals, and railroads lowered shipping costs which caused people to buy cheap goods that were produced in other places instead of more expensive goods that were produced locally. Between 1810 and 1840 the development of a national market prompted manufacturing which tripled the output’s worth. This increase in production created a change in industrial methods, such as the use of factories instead of handmade woven materials that families usually made.

Contemporary technology

Synthetic fibers such as nylon were invented during the 20th century and synthetic fibres.Linen is a textile made from the fibres of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. Linen is labour-intensive to manufacture, but when it is made into garments, it is valued for its exceptional coolness and freshness in hot weather.The word "linen" is cognate with the Latin for the flax plant, which is linum, and the earlier Greek linon. This word history has given rise to a number of other terms in English, the most notable of which is the English word line, derived from the use of a linen (flax) thread to determine a straight line.Textiles in a linen-weave texture, even when made of cotton, hemp and other non-flax fibers are also loosely referred to as "linen". Such fabrics generally have their own specific names other than linen; for example, fine cotton yarn in a linen-style weave is called Madapolam.

The collective term "linens" is still often used generically to describe a class of woven and even knitted bed, bath, table and kitchen textiles. The name linens is retained because traditionally, linen was used for many of these items. In the past, the word "linens" was also used to mean lightweight undergarments such as shirts, chemises, waistshirts, lingerie (a word also cognate with linen), and detachable shirt collars and cuffs, which were historically made almost exclusively out of linen. The inside cloth layer of fine composite clothing fabrics (as for example jackets) was traditionally made of linen, and this is the origin of the word lining.

Linen textiles appear to be some of the oldest in the world: their history goes back many thousands of years. Fragments of straw, seeds, fibers, yarns, and various types of fabrics which date back to about 8000 BC have been found in Swiss lake dwellings. Dyed flax fibers found in a prehistoric cave in Georgia suggest the use of woven linen fabrics from wild flax may date back even earlier to 36,000 BP.

Linen was sometimes used as currency in ancient Egypt. Egyptian mummies were wrapped in linen because it was seen as a symbol of light and purity, and as a display of wealth. Some of these fabrics, woven from hand spun yarns, were very fine for their day, but are coarse compared to modern linen.

Today linen is usually an expensive textile, and is produced in relatively small quantities. It has a long "staple" (individual fiber length) relative to cotton and other natural fibers.

Many products are made of linen: apron, bags, towels (swimmers, bath, beach, body and wash towel), napkins, bed linen, linen tablecloth, runners, chair cover, men's and women's wear.

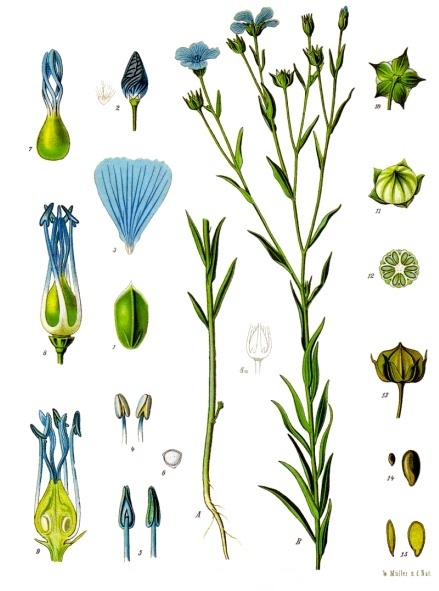

Flax fibre

Linen is a bast fiber. Flax fibers vary in length from about 25 to 150 cm (18 to 55 in) and average 12-16 micrometers in diameter. There are two varieties: shorter tow fibers used for coarser fabrics and longer line fibers used for finer fabrics. Flax fibers can usually be identified by their “nodes” which add to the flexibility and texture of the fabric.The cross-section of the linen fiber is made up of irregular polygonal shapes which contribute to the coarse texture of the fabric.

Properties

Linen fabric feels cool to the touch. It is smooth, making the finished fabric lint free, and gets softer the more it is washed. However, constant creasing in the same place in sharp folds will tend to break the linen threads. This wear can show up in collars, hems, and any area that is iron creased during laundering. Linen has poor elasticity and does not spring back readily, explaining why it wrinkles so easily.

Linen fabrics have a high natural luster; their natural color ranges between shades of ivory, ecru, tan, or grey. Pure white linen is created by heavy bleaching. Linen typically has a thick and thin character with a crisp and textured feel to it, but it can range from stiff and rough, to soft and smooth. When properly prepared, linen fabric has the ability to absorb and lose water rapidly. It can gain up to 20% moisture without feeling damp.

It is a very durable, strong fabric, and one of the few that are stronger wet than dry. The fibers do not stretch and are resistant to damage from abrasion. However, because linen fibers have a very low elasticity, the fabric will eventually break if it is folded and ironed at the same place repeatedly.

Mildew, perspiration, and bleach can also damage the fabric, but it is resistant to moths and carpet beetles. Linen is relatively easy to take care of, since it resists dirt and stains, has no lint or pilling tendency, and can be dry cleaned, machine washed or steamed. It can withstand high temperatures, and has only moderate initial shrinkage.

Linen should not be dried too much by tumble drying: it is much easier to iron when damp. Linen wrinkles very easily, and so some more formal linen garments require ironing often, in order to maintain perfect smoothness. Nevertheless the tendency to wrinkle is often considered part of the fabric's particular "charm", and a lot of modern linen garments are designed to be air dried on a good hanger and worn without the necessity of ironing.

A characteristic often associated with contemporary linen yarn is the presence of "slubs", or small knots which occur randomly along its length. However, these slubs are actually defects associated with low quality. The finest linen has very consistent diameter threads, with no slubs.

Measure

The standard measure of bulk linen yarn is the lea, which is the number of yards in a pound of linen divided by 300. For example a yarn having a size of 1 lea will give 300 yards per pound. The fine yarns used in handkerchiefs, etc. might be 40 lea, and give 40x300 = 12,000 yards per pound. This is a specific length therefore an indirect measurement of the fineness of the linen, i.e. the number of length units per unit mass. The symbol is NeL. (3) The metric unit, Nm, is more commonly used in continental Europe. This is the number of 1,000 m lengths per kilogram. In China, the English Cotton system unit, NeC, is common. This is the number of 840 yard lengths in a pound.

Production method

Details of the flax plant, from which linen fibers are derived

Mechanical harvesting of flax in Belgium. On the left side, flax is waiting to be harvested.

The quality of the finished linen product is often dependent upon growing conditions and harvesting techniques. To generate the longest possible fibers, flax is either hand-harvested by pulling up the entire plant or stalks are cut very close to the root. After harvesting, the seeds are removed through a mechanized process called “rippling” or by winnowing.

The fibers must then be loosened from the stalk. This is achieved through retting. This is a process which uses bacteria to decompose the pectin that binds the fibers together. Natural retting methods take place in tanks and pools, or directly in the fields. There are also chemical retting methods; these are faster, but are typically more harmful to the environment and to the fibers themselves.

After retting, the stalks are ready for scutching, which takes place between August and December. Scutching removes the woody portion of the stalks by crushing them between two metal rollers, so that the parts of the stalk can be separated. The fibers are removed and the other parts such as linseed, shive, and tow are set aside for other uses. Next the fibers are heckled: the short fibers are separated with heckling combs by 'combing' them away, to leave behind only the long, soft flax fibers.

After the fibers have been separated and processed, they are typically spun into yarns and woven or knit into linen textiles. These textiles can then be bleached, dyed, printed on, or finished with a number of treatments or coatings.

An alternate production method is known as “cottonizing” which is quicker and requires less equipment. The flax stalks are processed using traditional cotton machinery; however, the finished fibers often lose the characteristic linen look.

Linen uses range from bed and bath fabrics (tablecloths, dish towels, bed sheets, etc.), home and commercial furnishing items (wallpaper/wall coverings, upholstery, window treatments, etc.), apparel items (suits, dresses, skirts, shirts, etc.), to industrial products (luggage, canvases, sewing thread, etc.).It was once the preferred yarn for handsewing the uppers of moccasin-style shoes (loafers), but its use has been replaced by synthetics.

A linen handkerchief, pressed and folded to display the corners, was a standard decoration of a well-dressed man's suit during most of the first part of the 20th century.

The ancient Egyptians wore linen on a daily basis. They wore only white because of the extreme heat. Linen fabric has been used for table coverings, bed coverings and clothing for centuries.

History

Beds of some sort have been around for millennia. It is unknown when sheeting was first used to keep the sleeper comfortable but it is likely that the first true bed sheets were linen. Linen, derived from the flax plant, has been cultivated for centuries and was expertly cultivated, spun, and woven by the Egyptians. It is a laborious plant to cultivate but the finished fabric is perfect for bed sheeting because it is more soft to the touch than cotton and becomes more lustrous with use. Linen sheeting was made on conventional looms that were between 30-40 in (76.2-101.6 cm) wide, resulting in bed sheets that had to be seamed down the center in order to be large enough for use. Europeans brought linen culture to the New World; linen processing flourished in the Northeast and Middle Colonies for two centuries. However, because of the painstaking cultivation process, linens were difficult and time-consuming to make. Nevertheless, many seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century American women worked relentlessly producing linen goods—pillow cases, bed sheets, napkins, towels—for family use upon their marriage.

By about 1830 in the United States, cotton cultivation and processing was becoming well-established. Previously, it was difficult to remove the tenacious seeds found in short-staple cotton which grows easily in the American South. Eli Whitney's development of the cotton gin enabled the seeds to be stripped from the cotton wool easily and quickly; southern plantations immediately began growing the now-lucrative plant using enslaved labor. At the same time, New England textile mills were quickly adapting British cotton manufacturing technologies and were able to spin, weave, dye, and print cotton in huge quantities. By about 1860, few bothered to make bed sheets from linen anymore—why spend the time when cotton sheeting was cheap and easy to obtain?

Cotton fibers are produced from bales of raw cotton that are cleaned, carded, blended, and spun. Once loaded onto a section beam, the bobbins are coated with sizing to make weaving easier. Several section beams are loaded onto a single large loom beam. As many as 6,000 yarns are automatically tied onto old yarns by a machine called a knotter in just a few minutes.

Looms became more mechanized with human hands barely touching the products and bed sheets have been made on such looms since the later nineteenth century. Recent innovations in the product include the introduction of blended fibers, particularly the blending of cotton with polyester (which keeps the sheet relatively wrinkle-free). Other recent developments include the use of bright colors and elaborate decoration. Furthermore, labor is cheaper outside the United States and a great many bed sheets are made in other countries and are imported here for sale. Today, the southern states, particularly the state of Georgia, includes a number of cotton processors and weavers. Many of our American cotton bed sheets are produced in the South.

Raw Materials

If cotton is to be spun into yarn in the bed sheet manufactory, 480 lb (217.9 kg) bales are purchased from a cotton producer. This cotton is often referred to as cotton wool because it is fuzzy like wool. It is still dirty and includes twigs, leaves, some seeds, and other debris from harvesting. Other materials used in the weaving process include starches or sizing of some sort that is applied to the cotton threads to make them easier to weave. During the cleaning and bleaching process after the sheet has been woven, caustic chemicals and bleaches including chlorine and/or hydrogen peroxide solutions are used to remove all color before dyeing. Dyeing includes chemically-derived dyes (meaning they are not natural and not found in plants or trees but are created in laboratories) are used for standard coloration and color-fastness. |